Tai Sushi

A Comprehensive Overview of Seabream in Japanese Sushi Cuisine

タイすし 、 鯛寿司

Table of Contents

What is Tai?

In Japanese, the term tai 鯛 refers to fish from the sea bream family (Sparidae). This is a relatively large group that includes a wide range of species that can be used under this term for culinary purposes. The development of modern fishing and the associated convergence of international trade flows, as well as the advancement of science, have led to an increase in the number of species referred to as tai in Japanese in recent decades. The scientific “sea bream family” now comprises over 140 species. In addition, there are fish species that do not belong genetically to this group but also have tai in their Japanese name. According to Katsumi Suzuki, professor of ichthyology at Tokai University, 335 species have the term tai as part of their common name.[1]

From the perspective of Japanese cuisine, the red sea bream (Pagrus major), which is known in Japan as madai 真鯛 and whose name literally means “true sea bream”, is particularly noteworthy. In addition to madai, some other species are also important, such as kidai (Dentex hypselosomus) or kurodai (Acanthopagrus schlegelii).

Tai is widespread in Japan and plays an important culinary role, especially during traditional festivals. In this context, it is considered a lucky charm. It is also one of the most popular white-fleshed fish types for sushi and sashimi. During the season, high-quality specimens can reach high market prices.

Tai for Sushi or Sashimi

Tai (sea bream) is superior among whitefish. If you compare delicious tai and delicious hirame (flounder), then the tai wins hands down.

Jiro Ono, Sushi Chef (Sukiyabashi Jiro)[2]

Tai is highly prized as an ingredient in Japan and is nicknamed the “king of a hundred fish” 百魚の王. Madai is most commonly preferred for the preparation of sushi or sashimi. In addition, many other types of tai are also very tasty and common. It is common to indicate the specific type, such as “kinmedai sushi”, rather than just referring to the general generic term tai.

The bright white flesh is firm but still tender, the taste is slightly mineral, refreshing and accompanied by sweetish aromas. Fresh meat in particular can be somewhat watery, the moisture can be reduced by resting the meat for a few hours under cooling. In turn, the mineral taste loses some of its presence and the texture becomes softer. Between the meat and the skin lies a distinctive layer of fat. This subcutaneous fat is tasty and is appreciated for different preparation methods. The skin may be heated either by pouring boiling water over it or with the help of a torch. When heated, the subcutaneous fat layer begins to melt and releases additional flavors that harmonize beautifully with the taste of the raw meat.

Young Sea Bream as a Special Ingredient

Kasugo or kasugodai 春子鯛, sometimes simply kodai 小鯛, is a young red sea bream that is prized in Japanese cuisine for its delicate texture and subtle sweetness. Unlike adult sea bream, kasugo does not have the same fat content and is small, which makes handling and preparation a challenge. Caught in the early stages of its life, kasugo offers a tender, delicate texture and subtle sweet flavor that sets it apart from its adult counterparts.[3][4]

In Osaka, young red bream is also called chariko チャリコ and marinated with vinegar to make kodai suzushi 小鯛 雀鮨. Another dish that also uses chariko is suzume sushi 雀 寿司 from Wakayama Prefecture.[5]

Wild Capture vs. Aquaculture

The famous sushi chef Jiro Ono notes that he considers tai from aquaculture to be inferior in taste, so he does not serve tai to his customers. Furthermore, wild and high-quality tai has become rare and extremely expensive.[2] Wild caught tai differ to those from Aquaculture. Not only the limited freedom of movement and the usual high stocking density affect the condition of the fish, but also their food and climatic conditions to which they are exposed during farming.

Cultured tai are generally less firm in meat and have a higher fat content than wild specimens. These differences are not to be considered as basic quality characteristics, but rather represent a personal preference in taste.

Popular preparation methods for Tai

Matsugawa Method

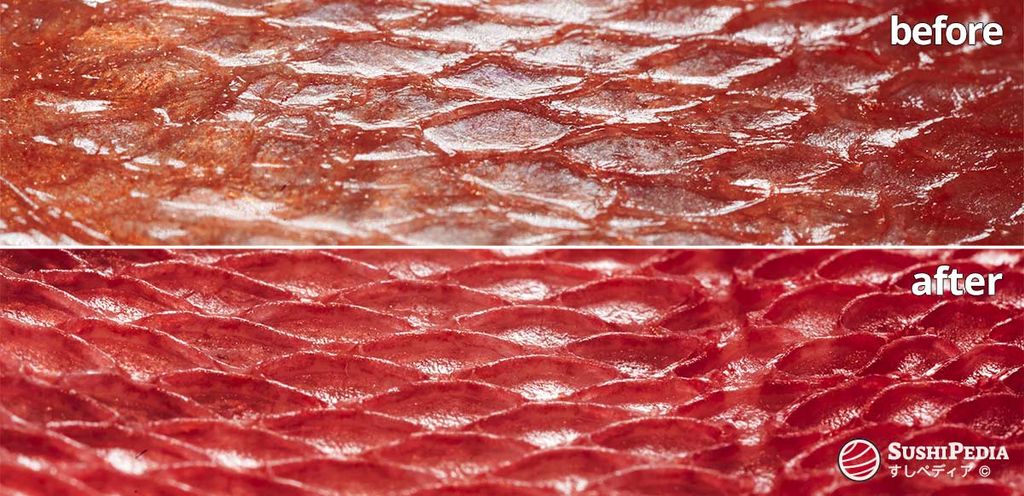

SushiPedia. Tai Sushi: Matsugawa Yubiki Zukuri. All rights reserved ©

Matsugawa zukuri is a preparation method that is mainly used for tai, isagi and bonito. Matsugawa means “making pine bark” in Japanese. After removing the scales from the fish, a characteristic pattern can be seen on the skin. When heated, this pattern becomes even more prominent and is visibly reminiscent of the bark of a Japanese pine.

In contrast to blanching or short frying (tataki たたき), the matsugawa method only heats the skin of the meat. For this purpose, the fish filet is placed either on a grid or a slanted kitchen board, covered with a thin cloth and then, for two to three seconds, doused with boiling water. The sudden heat causes the skin to contract and bend. To avoid cooking the raw meat, the filet is then immediately quenched in ice water.

Depending on the region, different names exist for the technique, the most common being matsugawa, shōhi, kawashimo, and yubiki.

Aburi Method

A similar effect can also be achieved by flame-torching, called aburi in Japanese. Compared to the matsugawa method, the skin becomes crispier, gets additional flavors from the burning process and stays slightly warm without cooking the underlying raw meat.

The skin can be prepared separately from the meat. Dried or roasted, it makes a tasty appetizer or side dish that goes well with Japanese alcohol.

Kombu-jime Method

The kombu-jime method originally comes from the Toyama prefecture. In this region, Japanese kelp or seaweed, called kombu, has always enjoyed a high status in the regional cuisine. Before the appearance of refrigerators, one of the methods of preserving fish was kombu-jime, which made it possible to transport the fish further into the inland.

The preservation by kombu-jime is not limited to tai, but is also suitable for many other fish species, but tai is especially suitable in terms of taste. To prepare tai no kombu-jime, the meat is sprinkled with salt and then wrapped in an airtight foil between slices of kombu. After up to one day under refrigeration, the meat has noticeably lost water, gained flavor and the full-bodied umami taste of kombu has been transferred to the meat. Afterward, the meat can be cut for the preparation of sashimi or sushi.

Best Season

Tai is fished all year round. In addition, the number of fish from aquaculture predominates, which are available all year round. The spawning time varies depending on the sea area and species. For wild madai from Japan the time between December and April can be considered the best season.

Depending on the season, tai gets a by-name in Japan. Specimens that have visibly gained fat during the spawning season are called sakura tai 桜鯛. Sakura is the term for the Japanese cherry blossom in spring, at this time of year, spawning of tai is imminent, and the fish have gained fat. The term mugiwara tai 麦わら鯛, which literally translates as “straw tai”, is used slightly derisively to describe an emaciated animal after the spawning season. Mugiwara means “straw” in Japanese and refers to the time of the wheat harvest, which overlaps with the spawning season. With a little imagination, this term can be seen as an analogy to the slender and emaciated body of the fish.

Tai in Japan

he history of eating tai dates back to ancient times. There is evidence that the consumption of sea bream in Japan dates back to the Jomon period, an era that lasted from around 14,000 to 300 BC. Archaeological finds indicate intact fish bones, which point to advanced fish processing techniques similar to filleting.[6] Literary references to tai can be found around 1300 years ago in classical texts such as the Man'yōshū and the Kojiki, which illustrates the high status of these fish in Japanese culture at the time. The spread of tai to the general population began around 300 years ago, during the Edo period. This was facilitated by the establishment of efficient distribution networks by the Shōgunate, the ruling authority of the time. Today, tai is still widely consumed, especially in western Japan, where it plays an important role in various culinary traditions. The versatility of tai makes it a favorite choice for many dishes, from sashimi and grilled to traditional dishes such as tai-meshi 鯛めし (on rice) and tai-sōmen 鯛そうめん (on noodles). In addition, its presence at regional festivals, such as its depiction in floats and traditional crafts, underlines its integral role in Japanese culture and testifies to its enduring importance.[5][7][8] Its status as a celebratory fish is also underpinned by the fact that the word tai is part of the Japanese expression for “happy” (omedetai おめでたい). The custom of eating a whole madai on various festive occasions has survived to this day. There is a custom of serving a entire madai, grilled with a pinch of salt, during okuizome お食い初め — the occasion that celebrates the hundredth day after the birth of a baby.

In Japan, tai is valued as a valuable ingredient, so over time some phrases related to tai have become part of everyday life. For example, they say “to catch a tai with a shrimp” (ebi de tai o tsuru 海老で鯛を釣る), as a metaphor for making a big profit with a small amount of money.

Differentiation of Tai by Color

In a traditional Japanese context, tai is categorized into three distinct color groups (tai sanshū 鯛三種), each defined by the specific hues associated with different species.

- Red to Pink Group: This category includes the red seabream, known as madai. Madai is highly prized in Japanese cuisine and culture, often featured in celebratory dishes due to its vibrant red to pink coloration, which symbolizes good fortune and joy.

- Yellowish Group: This group comprises the crimson seabream, called chidai, and the yellowback sea bream, known as kidai. These species are characterized by their distinctive yellowish hues, which can range from subtle amber to more pronounced golden shades. They are less common than the madai but are appreciated for their unique appearance and flavor.

- Black and Silver Group: This group includes the blackhead seabream, or kurodai, and the silver seabream, referred to as hedai. Kurodai is known for its dark, almost black head and silvery body, while hedai typically showcases a sleek, silver sheen. These seabreams are valued for their firm texture and are a staple in various regional dishes across Japan.

Characteristics & Ecology of Tai

Non-disclosed author. Pink Dorada fish isolated on white background Top view. All rights reserved ©

The family of the sea breams (Sparidae) belongs to the group of the perch-relatives, that consists of nearly 40 genera with more than 150 species. Some species of tai can reach an age of over 20 years. Due to the fact that the name tai includes some unrelated fish, a description of the characteristics and their natural environment is not possible in a comprehensive way. There are some popular fish, who don't belong to the genetic family of the sea-breams, whose Japanese name contains the designation tai, however, as for example the barred knifejaw (ishidai イシダイ), the splendid alfonsino (kinmedai キンメダイ) or the john dory (matōdai マトウダイ). Not genetically related, but sometimes considered belonging to the culinary group, is for example the Japanese snapper (aodai アオダイ), which is valued by chefs for the preparation of sushi or sashimi.

A part of the sea bream are so-called proterogyne hermaphrodites. Most proterogynous fish begin their life as a female and change their sex to male in the course of time.

Economy of Tai

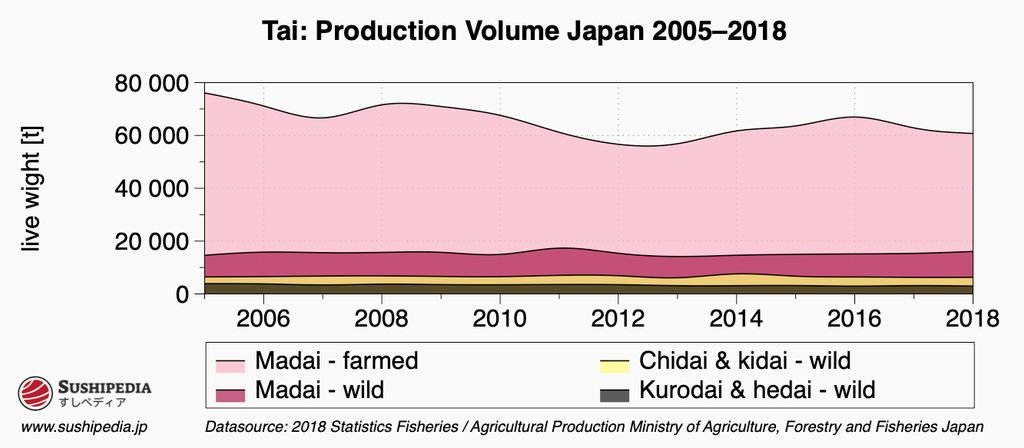

SushiPedia. Diagram of the global catch of tai. All rights reserved ©

Tai is of medium economic importance for Japanese fisheries. In 2018, tai accounted for less than 1% of total catches and 25% of total production from aquaculture. Most of the wild catches are landed in the prefectures of Nagasaki, Fukuoka and Ehime. The largest centers of breeding tai in aquaculture are located in Ehime and Kumamoto Prefectures.

Season Calendar for Tai

The calendar shown does not provide information on fishing times, but marks the periods in which tai is considered particularly tasty.

Video about Tai Sushi

External video embedded from: youTube.com. Credit Japanese chef cooks Japanese food. Japanese chef makes a Sea-bream sushi.

Species of Tai

The following species are regarded as authentic tai. Either historically, according to the area of distribution or according to the common practice in today's gastronomy:

In the following, those species are listed that can be considered as substitutes for authentic species with regard to tai. This can be based either on their genetic relationship or on their similarity in taste and appearance. The selection is subjective and is not strictly based on Japanese conventions, but also takes into account the practices in the respective areas where the Japanese dishes are prepared. This flexible approach allows for adaptation to local availability and preferences while preserving the core flavor and texture traditionally associated with tai. This list is not exhaustive due to the possible diversity of species worldwide.

Sources and Further Reading

- [1]鈴木 克美. 『そのタイは鯛なのか?』. 海のはくぶつかん 32 (1) 4-5. 2002

- [2]Shinzo Satomi. Sukiyabashi Jiro. Vertical Inc., New York. 2016

- [3]『ひときわ可憐な「㐂寿司」の小鯛。 | 「㐂寿司」の365日。 | 【公式】dancyu (ダンチュウ)』. Dancyu, President Inc., 2019-04-30. Source retrieved 4/18/2024

- [4]『三河湾は形原より、春を告げるカスゴ鯛』. Sushibito-Mitoku, 2021. Source retrieved 4/18/2024

- [5]Kumiko Morohashi, Yoshida Munehiro. 『日本人にとって特別な魚「鯛」』. 2023. Source retrieved 4/18/2024

- [6]Soichiro Kusaka, Fujio Hyodo, Takakazu Yumoto, Masato Nakatsukasa. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis on the diet of Jomon populations from two coastal regions of Japan. Journal of Archaeological Science 37 (8). 2010

- [7]Alexander Vovin. Manyoshu. 15, Book : a new English translation containing the original text, Kana transliteration, romanization, glossing and commentary. Global Oriental, Folkestone, Kent, U.K.. 2009

- [8]Donald L. Philippi. Kojiki. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. 2016

- 昌髙藤原. 『ぼうずコンニャクの市場魚貝類図鑑 (Bozu Konyaku's Market Fish and Shellfish Book)』. Bozu Konnyaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo ぼうずコンニャク株式会社東京, zukan-bouz.com、 2020. Source retrieved 12/27/2021

- 渋沢敬三. 『日本魚名集覧第三部魚名に関する若干の考察(1943)、 のちに『日本魚名の研究』(1959)として復刻]には「なんとかダイ』. 日本常民文化研究所彙報 2 (56)

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2023-1

Image Credits

- SushiPedia. Tai Sushi: Matsugawa Yubiki Zukuri. All rights reserved ©

- SushiPedia. Tai Sushi. All rights reserved ©

- Non-disclosed author. Pink Dorada fish isolated on white background Top view. All rights reserved ©

- SushiPedia. Diagram of the global catch of tai. All rights reserved ©