Unagi Sushi

A Comprehensive Overview of Freshwater Eel in Japanese Sushi Cuisine

ウナギすし 、 鰻寿司

Table of Contents

What is Unagi?

In Japanese, the word unagi 鰻 generally refers to a freshwater eel (Anguilla). In the cultural and culinary context of Japan, unagi 鰻 refers specifically to the Japanese eel (A. japonica), a species that plays a special role in both Japanese cuisine and culture. The Japanese eel is highly prized for its culinary merits and its status as a delicacy, and is a central component of many traditional dishes. It is considered one of the most expensive edible fish in Japan.[1] In professional contexts, especially in trade and scientific circles, the more specific name nihon unagi 日本鰻 is preferred to the more general term unagi. This more specific term emphasizes the exact species, the Japanese eel, and differentiates it from other freshwater eel species.

Freshwater eel is not traditionally considered a classic sushi ingredient. In modern cuisine, however, it is often served as sushi, especially outside Japan. The economically most important eel species are the European eel (A. anguilla), the American eel (A. rostrata) and the Japanese eel (A. japonica). The European eel and the American eel are mainly found in North America and Europe, while the Japanese eel is mainly found in East Asia. These species are particularly prized for their taste and texture and are central to many traditional dishes in their respective regions. Japanese eel, known for its tender meat and rich flavor, is primarily used in traditional Japanese cuisine, especially in dishes such as unagi shirayaki (grilled eel) or unagi kabayaki (eel marinated in a sweet and sour soy sauce and then grilled). These types of preparation are particularly popular in sushi restaurants. European eel, although less commonly used in sushi dishes, is still used in some European countries to prepare sushi and other Japanese dishes. Both species are highly prized for their flavor profile and texture and play a central role in gastronomy and eel-based dishes.

Unagi for Sushi or Sashimi

Unagi is rich in protein, vitamins, and minerals. The cooked meat has an unmistakable taste which distinguishes it significantly from other fish. The prepared meat of unagi is very soft and fluffy, pleasant on the palate and usually without a fishy or earthy aftertaste. The high fat content gives it a full-bodied flavor that can be enjoyed with a savory soy sauce known as kabayaki, or with salted unagi known as shirayaki.

The mucous layer of the unagi can emit an unpleasant odor depending on the habitat and food. Therefore, both natural captive and farmed unagi are placed in clean water for one or two days before they are killed. The Japanese method of preparation of unagi follows several successive steps. First, the eel is cut open and filleted either at the head or on the ventral side, starting lengthwise. The meat is then cut into pieces of equal size, placed on skewers and gently roasted over charcoal. In the next step, the fillets are steamed and then dipped in sauce to be roasted again on the grill.

Occasionally, the prepared meat from the unagi is sprinkled with Japanese pepper (sansho サンショウ) to give the meat a fresh smell. In addition, sansho is said to have a digestive effect which is supposed to support the absorption of the fatty unagi meat. For the preparation of unagi nigiri sushi, it is recommended to refrain from this and prefer sesame (goma ゴマ) or don't use any garnish at all.

Unagi No Tare: The Traditional Japanese Eel Sauce

SushiPedia. Unagi sashimi with eel sauce (unagi no tare). All rights reserved ©

Although unagi can be enjoyed without sauce (tare たれ), it is usually served with a thick broth made especially for unagi, called unagi no tare うなぎのたれ. In the days when unagi sauce was not yet produced commercially in large quantities, it was considered an indication of the chef's skill. Nowadays, self-made unagi sauce is rarely found, or if it is, only in high-end restaurants.

The basic ingredients of unagi no tare are soy sauce, mirin, sugar, and sake. The taste and consistency are similar to teriyaki sauce. Although unusual, the taste of the sauce makes it an ideal accompaniment to grilled meat dishes.

Comparison of Freshwater Eels (Unagi) and Conger Eels (Anago)

Unagi is not considered a traditional ingredient for making sushi in Japan. Only rarely, or on advance order, you can find unagi as handmade nigiri in Japanese sushi restaurants. Analysis of Google search queries, as well as the evaluation of the advertisements of Japanese sushi chains, indicate an increasing demand for unagi nigri sushi in Japan. More common is the use as an ingredient for pressed sushi (oshizushi). In contrast, the conger eel (anago) is an essential part of the seasonal menu of a restaurant. Outside Japan, especially in North America and Europe, the situation is the opposite. Since anago is rarely actively fished outside of Northeast Asia, it is simply too complicated or nearly impossible for most sushi chefs to obtain fresh anago. Thus, mostly imported, frozen and (in the worst case) already industrially prepared unagi is used. Only in high-quality restaurants, fresh and regionally available river eel is prepared.

Compared to anago, unagi is more tasty, fatty and meaty. Moreover, unagi is considered a higher quality delicacy in Japan and is therefore more expensive. In terms of taste, unagi differs from anago by its more intense and full-bodied taste. The common opinion is that anago, because of its lighter taste, harmonises better with soured sushi rice and is therefore the preferred choice for making sushi.

Best Season

Although unagi is traditionally eaten on the “day of the ox” (doyō no ushinohi), late autumn until early winter is considered the best season. During this time, fish build up fat reserves in preparation for winter, when they hibernate in burrows and holes.

Even though unagi is most tasty towards the beginning of winter, unagi is traditionally appreciated in the middle of summer. In Japan they say unagi gives you strength and endurance, which you need especially during the Japanese summer heat to prevent exhaustion.

Wild Catch vs. Aquaculture

Wild-caught unagi (ten’nen unagi 天然ウナギ) differs in taste from its aquaculture counterpart (yōshoku unagi 養殖ウナギ). It is characterized by a lighter, less fatty taste. The meat is firmer and the animals tend to be larger. In addition, wild-caught unagi is often kept in acidic water for a certain period of time to reduce any off-flavor. In contrast, aquacultured unagi has a softer taste that is free of earthy or boggy flavors and offers a consistent taste quality.

Unagi in Japan

Archaeological excavations from the Jomon period show that unagi was already used as a source of food in ancient times. During the expansion of Edo, unagi was considered the food of ordinary workers who caught it during the draining of Tokyo Bay. While unagi was mainly sold in mobile food stalls (yatai 屋台) along the roadside until the dawn of the Meji period, nowadays unagi is mainly found in specialty restaurants.

In Japan, the term unagi nobori (うなぎのぼり), which can be freely translated as “climbing as an eel”, is similar to the expression “skyrocketing”. It means that the ascent or rise of something or someone progresses rapidly and is usually subject to special conditions and may only be temporary. The term is derived from the habit of unagi that after a certain time they return from the sea and hike up the mountain rivers to return to the ponds and lakes where they originally lived.

Unagi on the “Day of the Ox”

In Japan, it is a custom to eat unagi on the “day of the ox” (doyō no ushi no hi 土用の丑の日), a celebration day that is repeated annually at the end of July. The origin of this custom is not clear, the theories range from the mention in poems, to the invention by a writer from the Kyōhō period, to the theory that the Japanese characters for ox (ushi うし) resemble two eels.

Characteristics & Ecology of Unagi

SushiPedia. reshwater Lagoon Ecosystems: Habitat for Eels. All rights reserved ©

Eels of the genus Anguilla are distributed in various regions worldwide, with their presence concentrated in specific geographical and ecological conditions. The European eel (A. anguilla) is found in many parts of Europe. Related species exist in North America, east of the Appalachians, and in East Asia, particularly in Japan and the coastal areas of China. The river basins of south-eastern Australia and New Zealand are also each home to their own eel species. The American eel (A. rostrata) is a species related to the European eel. This species is primarily found in the rivers and coastal areas east of North and Central America, from Greenland to Brazil. The Japanese eel (A. japonica) is a species belonging to the same genus as the European and American eels, characterized by its unique distribution and biological features. Found predominantly in the waters of East Asia, particularly along the coasts and rivers of Japan, Taiwan, and parts of mainland China, the Japanese eel plays a significant role in both the ecosystem and local culture. Similar to its relatives in the genus Anguilla, the Japanese eel has a complex life cycle that involves vast migrations. There are other eel species in the tropical regions of South and Southeast Asia, New Guinea, eastern Africa and Western Australia. These species prefer river basins that flow directly into deep sea areas and avoid rivers whose estuaries merge into extensive shallow seas.

Eels are not found in the icy waters of the polar regions, which explains their absence in the cold polar regions. They are also absent from the southern Atlantic and the eastern part of the Pacific. This distribution pattern also excludes adjacent land masses, which include western and central North America, West, North and Central Africa as well as Central and South America.

The Life Cycle of the Genus Anguilla: From Marine Spawning Grounds to Freshwater Habitats

The life cycle of the freshwater eel of the genus Anguilla begins in the depths of the oceans, particularly in the Sargasso Sea for the European eel and the American eel. In Japan, an area strongly influenced by the Indo-Pacific currents, four eel species are native: the Japanese eel (A. japonica), the giant eel (A. marmorata), the Indonesian shortfin eel (A. bicolor) and the uguma eel (A. luzonensis).[2] The Japanese eel is mainly found in East Asia, including Korea, mainland China and the Philippines. Recent studies suggest that its spawning grounds are close to the Mariana Trench. The giant eel has a more extensive range, extending from the East African coast to French Polynesia, although it is thought to spawn in the deep-sea regions south of the Philippines.

The spawning phase takes place far away from the freshwater habitats into which the eels later migrate. After hatching, the larvae, known as leptocephali, drift with the ocean currents and begin a migration to the coastal regions that lasts from several months to several years. During this phase, they undergo a metamorphosis in which they develop from transparent larvae into glass eels that migrate upstream in freshwater or brackish water habitats.

Upon reaching suitable habitats, the glass eels transform into pigmented eels and adapt to life in rivers, lakes, or marshes. During this growth phase, which can last several years depending on the environmental conditions and species, the eels reach their full size.

A characteristic feature of the life cycle of freshwater eels is the semelparous reproductive strategy, in which individuals reproduce once in their lifetime and then die. Adult eels migrate to their spawning grounds in the ocean, where reproduction takes place. This migration marks the transition from the freshwater or brackish water phase back into the marine environment. After reproduction, the eels die. The cycle thus encompasses both marine and limnic life stages and underlines the ecological adaptability of eels and their importance for the biodiversity of aquatic systems.

Economy of Unagi

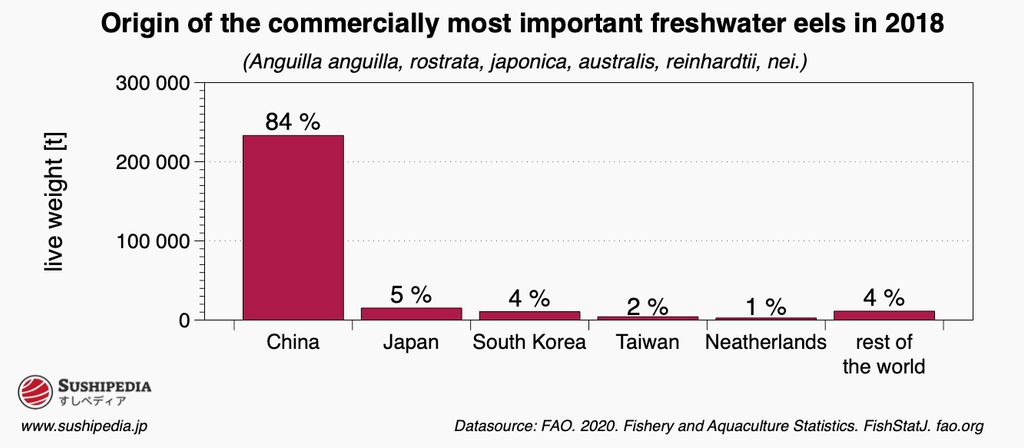

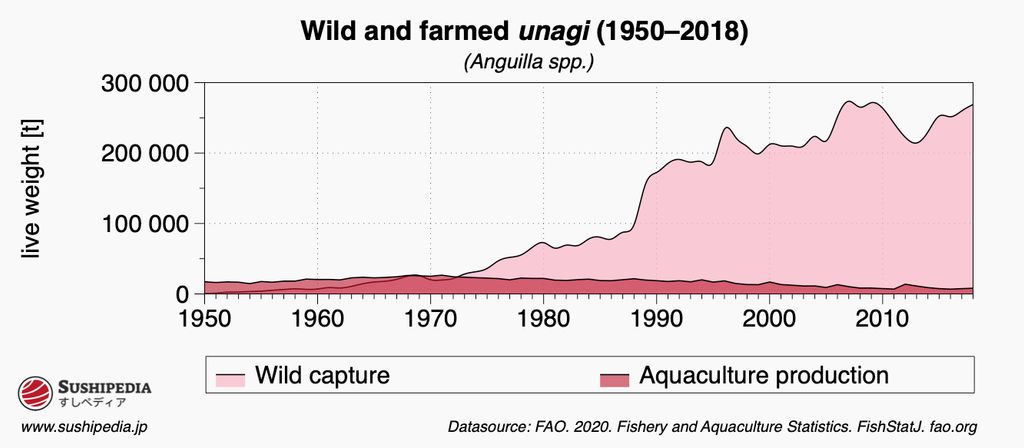

Many fish belonging to the freshwater eel family (jap. unagi-ka) are considered commercially important seafood. In the last decade, the increase in industrial aquaculture breeding has shown enormous growth rates, with the largest production centers being located in East Asia.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), around 97 percent of unagi production came from aquaculture in 2018.

Sustainability

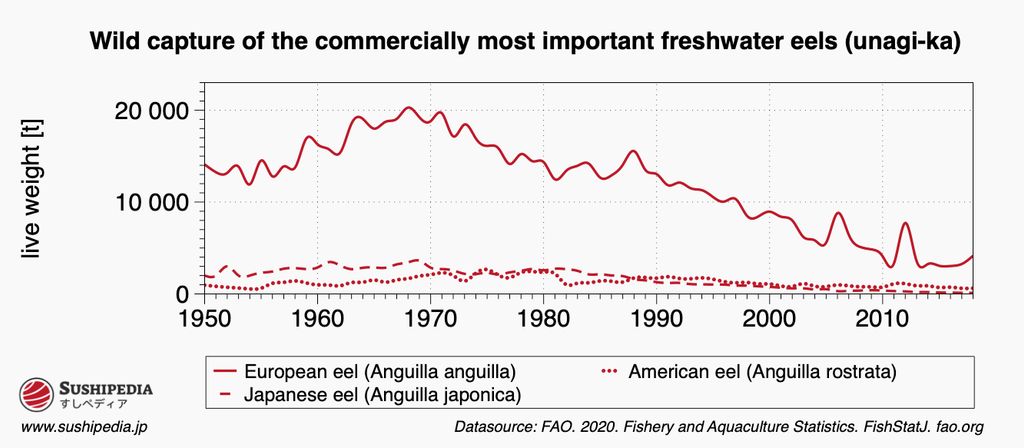

SushiPedia. Decline in Wild Capture of European and American Eels (1950–2018). All rights reserved ©

Unagi is a popular edible fish that has been fished in Japan and Europe for centuries and is valued as an ingredient. Growing consumer demand and the convergence of international trade flows in recent decades have increasingly contributed to its threat. The European eel is now considered to be in danger of extinction, while the Japanese and American eel, among others, are considered to be highly endangered. Since February 2013, the Japanese Ministry of Environment has officially listed the Japanese eel as a threatened species.[3] All species relevant as unagi are severely decimated in population size, although about 95 % of the consumed ungagi come from aquaculture, they are not bred in captivity. Instead, young eels (silver or glass eels) are taken from the wild and then reared in closed cultures and fattened until they are ready for slaughter.

SushiPedia. Global Production Share of Freshwater Eels by Country in 2018. All rights reserved ©

Besides the excessive number of wild catches, the destruction of natural habitats, illegal fishing, and the fishing of juveniles for aquaculture poses an existential threat. Until the development of a so-called “complete aquaculture”, for which no glass eels have to be taken from the wild, a consumer must decide for himself to what extent each piece of unagi he orders affects the survival of the entire species.

Aquaculture

SushiPedia. Production Trends of Wild and Farmed Unagi (Anguilla spp.) from 1950 to 2018. All rights reserved ©

European eels are exported to China in significant quantities as juveniles, known as glass eels. In China, these juveniles are reared in aquacultures. Once they have reached marketable size, they are often exported back to Europe and other parts of the world. This trade route is partly a response to the declining stocks of wild eels in Europe and the high demand for adult eels on the global market.

The common practice is to raise juvenile eels (glass eels) from wild stocks in aquaculture. It is still not possible to breed commercially viable unagi in captivity. Artificially fertilized eggs and successful hatching have been repeatedly achieved under laboratory conditions. In 2002, the Aquaculture Research Institute at the Fisheries Research Centre in Mie Prefecture succeeded for the first time in the world in developing larvae into glass eels.[4] Research continues to face serious problems in terms of food supply, resource consumption and the need for hormonal feminization of the spawn. Among the main issues that researchers are facing is the need for shark eggs as a food source for juvenile eel immediately after hatching, the need for daily water changes and hormonal feminization, as the vast majority of fish fry from artificial environments are male.[5]

Season Calendar for Unagi

The calendar shown does not provide information on fishing times, but marks the periods in which unagi is considered particularly tasty.

Video about Unagi Sushi

External video embedded from: youTube.com. Credit Eater. Chef Kanejiro Kanemoto Is Japan's Grilled Eel Master — Omakase.

Species of Unagi

The following species are regarded as authentic unagi. Either historically, according to the area of distribution or according to the common practice in today's gastronomy:

In the following, those species are listed that can be considered as substitutes for authentic species with regard to unagi. This can be based either on their genetic relationship or on their similarity in taste and appearance. The selection is subjective and is not strictly based on Japanese conventions, but also takes into account the practices in the respective areas where the Japanese dishes are prepared. This flexible approach allows for adaptation to local availability and preferences while preserving the core flavor and texture traditionally associated with unagi. This list is not exhaustive due to the possible diversity of species worldwide.

Sources and Further Reading

- [1]Francesca Ottolenghi, Cecilia Silvestri, Paola Giordano, Michael B. New, Alessandro Lovatelli. Capture-based Aquaculture - The Fattening of Eels, Groupers, Tunas and Yellowtails. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2004

- [2]Tomohiro Kita, Kazuki Matsushige, Shunsuke Endo, Noritaka Mochioka, Katsunori Tachihara. First Japanese records of Anguilla luzonensis (Osteichthyes: Anguilliformes: Anguillidae) glass eels from Okinawa-jima Island, Ryukyu Archipelago, Japan. Species Diversity 26. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.12782/specdiv.26.31.

- [3]Publication of the Fourth Red List (Brackish and Freshwater Fishes) 第4次レッドリストの公表について(汽水・淡水魚類). Ministry of the Environment (MOE) (環境省), Tokyo (東京), env.go.jp. 2013

- [4]『“世界初の「ウナギの完全養殖」、ついに成功!〜天然資源に依存しないウナギの生産に道を開く〜 ”, プレスリリース (The world's first 'complete eel farming' finally succeeds! Paving the way for eel production that does not depend on natural resources, Press Release)』. Fisheries Research and Education Center (水産総合研究センター), Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Research Council (AFFRC) (農林水産技術会議), affrc.go.jp. 2010. Source retrieved 12/26/2020

- [5]Complete eel farming achieved (ウナギ 完全養殖達成). Fisheries Research Agency News, FRANEWS 23 4-20. 2010

- Fisheries and Aquaculture Department. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics. Global production by production source 1950-2019 (FishstatJ). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. 2021. Source retrieved 5/12/2021

- 辻泰弘編. 『東西美味の品格-調理法で比べる東西の味わい-鰻 (A Taste of East and West - Comparing East and West by Cooking Methods - Eel)』. Shogakukan (小学館). 2012

- 『Kawaei eel | Akabane Kawaei』. Kawaei Akabane, 2004. Source retrieved 1/27/2024

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2023-1

Image Credits

- SushiPedia. Decline in Wild Capture of European and American Eels (1950–2018). All rights reserved ©

- takaokun. IMG_5614 Unagi Nigiri. flickr.com. Some rights reserved: Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

- SushiPedia. Unagi sashimi with eel sauce (unagi no tare). All rights reserved ©

- SushiPedia. Global Production Share of Freshwater Eels by Country in 2018. All rights reserved ©

- SushiPedia. Production Trends of Wild and Farmed Unagi (Anguilla spp.) from 1950 to 2018. All rights reserved ©

- Unknown author. Unagi (Eel) Nigiri Sushi. All rights reserved ©

- SushiPedia. reshwater Lagoon Ecosystems: Habitat for Eels. All rights reserved ©

- Jeremy Keith. Unagi. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adactio/89365094/. Some rights reserved: Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)