Tako Sushi

A Comprehensive Overview of Octopus in Japanese Sushi Cuisine

タコすし 、 蛸(鮹・章魚)寿司

Table of Contents

What is Tako?

In Japanese cuisine, tako 蛸 refers to the group of “true octopuses”, which are scientifically classified as Octopodidae. The East Asian common octopus (Octopus sinesis), whose Japanese name madako literally means “true octopus”, is one of the species most commonly used in Japanese cuisine. When people in Japan talk colloquially about tako, they often mean this species. However, the variety of octopods caught in Japanese waters also includes other species such as the North Pacific giant octopus or the long arm octopus and others that are popular in different regions.

Tako is one of the classic cooked ingredients in sushi cuisine. Unlike many other sushi ingredients that are served raw, octopus is usually cooked to make its texture softer and more tender.

Tako for Sushi or Sashimi

Tako is usually not eaten raw (nama-dako 生蛸), but cooked (yude-dako ゆでだこ). After cooking, however, it becomes a prized ingredient in various Japanese dishes such as sushi and sashimi. The cooking process changes the consistency of the octopus, making its texture softer and more pleasant to eat. If tako is left to rest after cooking until it has cooled to a temperature between room and body temperature, it reaches its peak flavor. Lowering the temperature further by cooling or freezing, on the other hand, impairs the flavors and texture.

When prepared correctly, tako sushi or sashimi is pleasantly meaty, tender, juicy and the consistency of the slightly crispy suckers offers an exciting sensory variety. When preparing nigiri sushi, cuts are made in the meat, either conspicuously or discreetly, to increase its suppleness. This allows the firmer meat to better follow the shape of the rice ball. This process is known as kakushi bōchō 隠し包丁. In order to adhere better to the rice, a wavy pattern, similar to a washboard, is added to the meat when cutting. This technique is known as sazanami kiri さざなみ切り, which literally means “wave cut”. Alternatively, the section of tentacle can also be attached with a wrapped strip of dried seaweed.

Compared to many other ingredients for sushi or sashimi, the preparation of tako is more time-consuming, but not necessarily more complex. Nevertheless, tako loses a lot of its taste and texture if it is stored for too long, chilled too much or prepared without the necessary finesse. The taste is intense, but without being overpowering. It is therefore recommended to avoid using seasoning sauce, which is unfortunately often used in “simple” sushi restaurants.

Best Season

Depending on the region and population of the octopus the animals spawn at different times. In addition, it has been observed that some populations spawn twice a year. In general, it can be said that the vast majority are most palatable in winter. The tako caught in early summer is also called “straw octopus” (mugiwara dako 麦わらダコ), named after the season in which fishermen traditionally wore straw hats when they went fishing.

Tako in Japan

The consumption of octopus in Japan can be traced back to prehistoric times. Due to technical progress in the last century, in particular the use of larger ships and the professionalization of fishing methods, octopods have become an extremely popular ingredient in Japanese cuisine. The most important species for fishing in Japan are madako, mizudako, yanagidako and īdako. In some prefectures, tenagadako and kumodako are also fished on a small scale. Tako is an essential part of Japanese cuisine and is used in many dishes, for example as a garnish marinated in vinegar (tako no sunomono たこの酢の物) or as a filling for deep-fried dough balls, called takoyaki. Madako, mizudako and yanagidako are mainly used as an ingredient for sushi or sashimi. Whereas īdako is typically cooked whole, as part of a boiled pot dish known as oden in Japanese, as well as for special dishes such as tako no tamago, which is aimed at the mature ovaries of females.[1]

As Japan's demand for tako cannot be met from domestic waters, related species must inevitably be imported from the Atlantic and the northwest African continent. Imports of common octopus from the Mediterranean account for about half of Japan's import market. In Japanese supermarkets, this species is labeled together with its country of origin as madako, a term also used for the native madako. It is believed that the high volume of imported common octopus labeled as madako means that declines in endemic populations, which are also labeled as madako, are less visible.[1] To make consumers aware of the critical situation, it has been proposed that imports of Mediterranean common octopus be labeled with the specific name chichūkai madako (literally “Mediterranean octopus”).[2]

Myth of the Poisonous Tentacle Tips

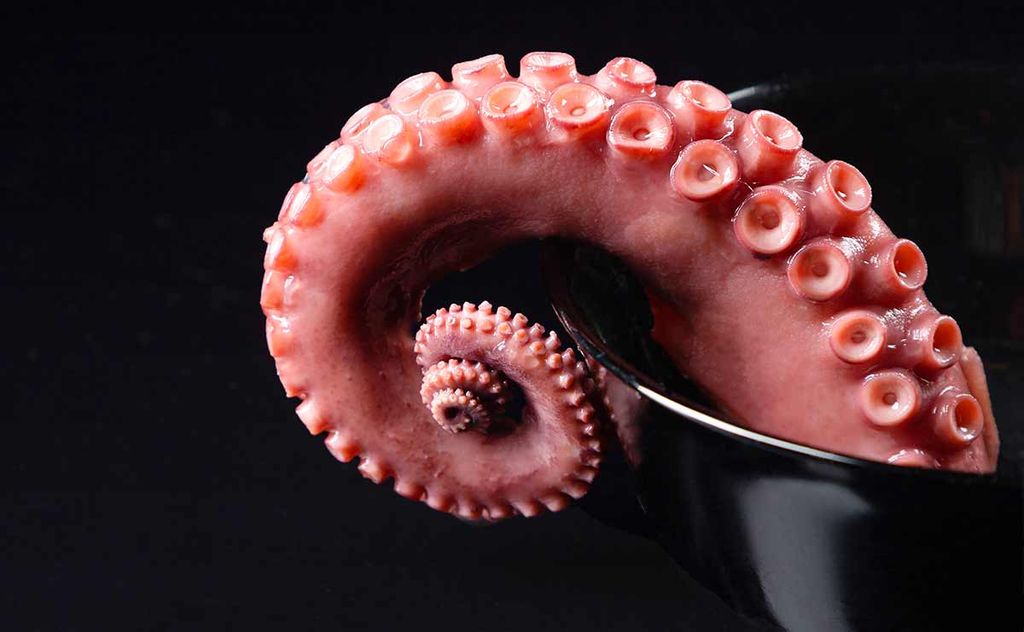

Non-disclosed author. Tentacle of stew octopus on dark background.. All rights reserved ©

There is still a persistent opinion, especially among older Japanese, that poison would accumulate in the tips of the tentacles. This “urban legend” is based neither on facts nor on scientific research. Rather, there is evidence that poisoning has occurred because the tentacle tips can be a potential breeding ground for bacteria. The size and distance of the suckers become smaller the closer they are to the tip of the tentacle. The nature of the tip generally not only makes cleaning more difficult, but also promotes the growth of bacteria if the small suction cups are not cleaned properly. By boiling the tako sufficiently, the danger of a bacterial infection is avoided, but remaining dirt or sand will have a disturbing effect on consumption.

The tips of the male mating tentacles (lat. Hectocotylus) are deliberately removed as they lack the suckers at the tip and are less attractive. The fact that this is used during the reproductive period to transport sperm capsules into the female body also plays a role.

Regional Brands (地域ブランド)

SushiPedia. The Art of Sushi Preparation: Featuring Yudako. All rights reserved ©

Tako is caught all over the coastal waters of Honshu, the biggest catch is landed in Akashi town every year. The fishing grounds are located on the west side of the Akashi Strait and in the eastern bay of Osaka. The octopus from Akashi enjoys an excellent reputation in Japan. This is due to the topography and the tides in the Akashi Strait, where the tide flows back and forth twice a day. The currents can reach high speeds, so the Akashi octopus grows into a muscular animal in the Strait of Akashi while chasing its prey through the fast currents.

The city of Hitachinaka in Ibaraki Prefecture produces the largest quantity of processed tako in Japan. Every year on August 8th, “Octopus Day” (tako no hi) is celebrated there, when the whole city is lined with stalls selling steamed (mushi 蒸し) or pickled octopus (su tako 酢たこ).

SushiPedia. Japanese Brands of Tako. All rights reserved ©

Tako Trivia

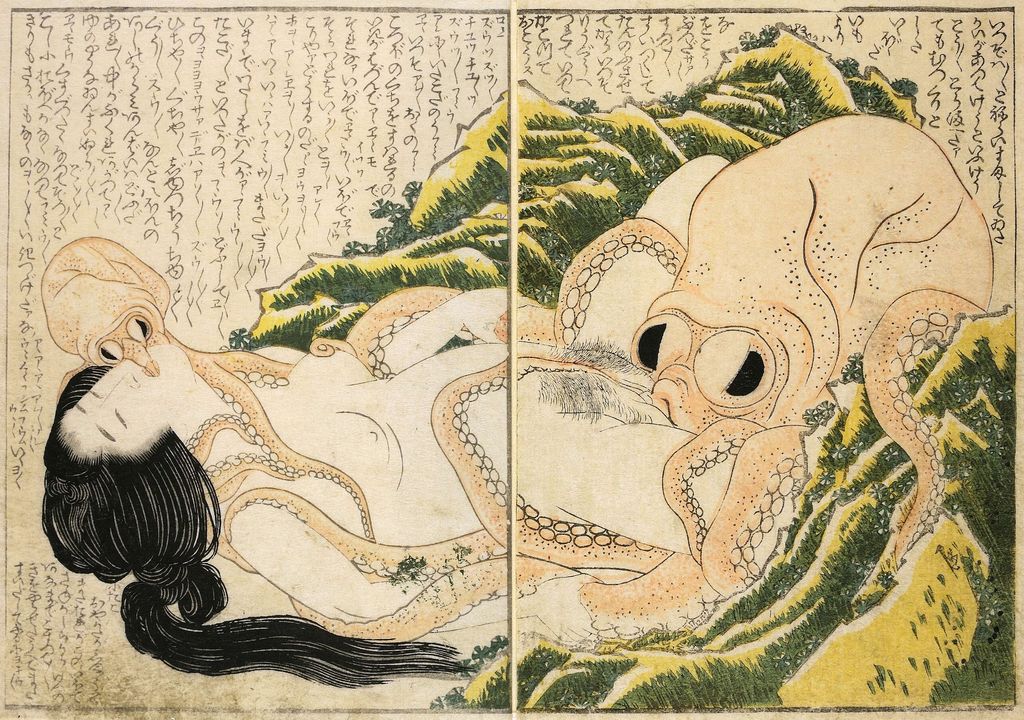

Katsushika Hokusai. 蛸と海女の図. wikimedia commons. Some rights reserved: public domain

After the end of the Second World War, Japan adopted a law restricting the display of sexual acts, in particular the display of genitals. Inspired by the works of the 18th century artist Katsushika Hokusai, octopus tentacles now found their way into the production of contemporary erotica and pornography. Hokusai's most famous works include “The Octopus and the Shell Diver” (tako to ama 蛸と海女), which shows a young woman during sexual intercourse with two octopods. After all, Japanese law only prohibited the depiction of human genitalia, not one or more tentacles.

Tako o Tataku: Beating the Octopus

The technique of tako o tataku タコを叩く, which translates as “beating the octopus”, is a traditional preparation method in Japanese cuisine that is used far beyond the borders of Japan by other peoples who eat octopods. This procedure is designed to tenderize the often tough meat by loosening the muscle fibres. As the meat is predominantly muscle, with no specific fiber direction, beating helps to soften the texture. Traditionally, the animal is beaten against hard surfaces such as stones, or softer beating instruments are used.

Alternatively, the meat can also be kneaded or massaged intensively. In Japan, this is often done with the help of a cut Japanese radish, daikon in Japanese. The daikon allows more pressure to be applied evenly to the meat without damaging the surface. It is also assumed that enzymes such as the daikon's myrosinase can break down the proteins in the octopus meat, making the meat more tender. Nowadays, octopus is also regularly frozen in advance, as the slow freezing process causes less damage to the cell structures of the meat, resulting in a more tender consistency after thawing.

Characteristics & Ecology of Tako

Non-disclosed author. big octopus swims in an aquarium. All rights reserved ©

Tako are characterized by exceptional adaptability and versatility in different marine ecosystems. These mollusks are known for their eight long arms, which are covered with suction cups that allow them to hold on and skillfully manipulate their prey. Octopods also possess a remarkable nervous system and brain, making them the most intelligent of all invertebrates. Ecologically, they play an important role as both predator and prey in their habitat. They feed on a variety of smaller marine creatures, thereby influencing the population of other species and contributing to the health of the ecosystem. Their ability to change the color and texture of their skin serves not only as camouflage from predators, but also to communicate with other octopods.

The distribution area extends over many marine regions worldwide. From cold waters such as those around Alaska and Norway to the warmer waters of the Pacific and Indian Oceans and the Mediterranean, these animals can be found in a variety of habitats. They often prefer coastal regions where they can hide in crevices and under overhangs. These locations offer protection from predators and a rich variety of food. Octopods can also be found in deeper waters, where they live at depths of up to several hundred meters.

Common Octopus

The common octopus reaches a total length of up to one meter. Characteristic is its sack-shaped body without shell and supporting skeleton with its eight muscular arms (tentacles) covered with double rows of suckers. The common octopus is found worldwide in the seas of the tropical and temperate zone, its distribution extends to the Pacific Ocean, the Sea of Japan, the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea and the rest of the world. It inhabits rocky reefs and bays facing the open sea. During the day, it hides in rock holes and crevices on the sea floor and is active at night, feeding mainly on crustaceans, bivalves and snails. The usual age is up to two and maximum three years, until they die after spawning and breeding.

Scientists suspect that the worldwide populations of the common octopus could be several independent species, whose differentiation can only be achieved by molecular genetic diagnostics and not by external appearance. Studies have shown that the Japanese madako is a separate, albeit closely related, species to the Atlantic and Mediterranean population.[3]

The Taxonomic Reassessment of Octopus Vulgaris and Its Implications

Octopus sinensis, which was once classified as a synonym of O. vulgaris due to morphological similarities, has been recognized as a separate species since 2017. Originally, both species were grouped together under the scientific name O. vulgaris. However, research conducted by Gleadall in 2016 concluded that O. sinensis is a distinct species, native to different regions than O. vulgaris, which is found in the Mediterranean and Atlantic.[3] This clarification was based on nuanced differences between the species, despite their apparent morphological similarity. The assumption that O. vulgaris is a species widely distributed in temperate to tropical waters was disproved by the discovery of this cryptospecies. As a consequence, several species such as O. sinensis, O. tetricus and O. cf tetricus in the Pacific; type I and II in the western Atlantic; and type III in the Indian Ocean around South Africa are now recognized, so that the O. vulgaris species group is now regarded as six different species. The tropical western Central Atlantic harbors a cryptic species thought to be Type I.[4]

The reclassification of O. sinensis means that in many cases the trivial name Madako is used for O. vulgaris. This taxonomic change raises the question of whether O. vulgaris or O. sinensis will establish its own trivial name in Japanese. The use of madako could continue until a new name is established, depending on its acceptance in the scientific community. A newly established Japanese common name would help to clarify the distinction between species and improve the accuracy of communication in Japanese non-scientific publications or trade.

Economy of Tako

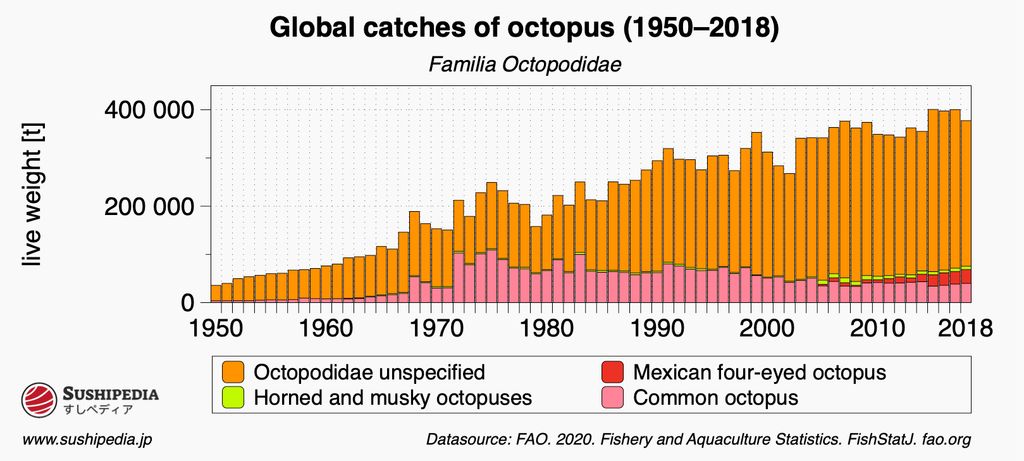

SushiPedia. Global Capture Trends of True Octopuses. All rights reserved ©

Octopods are considered a high-value species that is actively fished in many regions of the world, especially in Asia and the West Pacific. Only four octopus species names are currently listed in the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nationss (FAO) catch statistics, the rest are classified as unidentified octopus. The common octopus is one of the most valuable octopods and is usually marketed fresh or frozen.

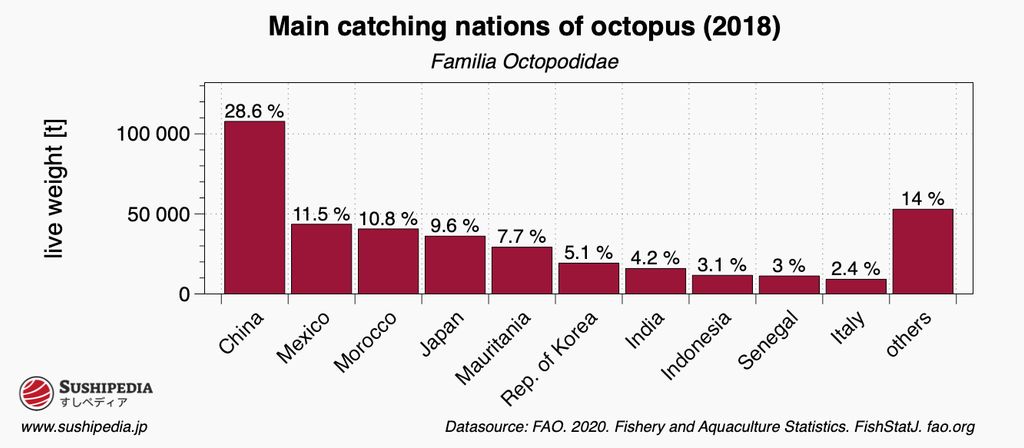

SushiPedia. Major Catching Nations of True Octopuses in 2018. All rights reserved ©

Season Calendar for Tako

The calendar shown does not provide information on fishing times, but marks the periods in which tako is considered particularly tasty.

Video about Tako

External video embedded from: youTube.com. Credit Eater. How Master Sushi Chef Tomonori Nagai Prepares an Octopus for His Omakase — Omakase.

Species of Tako

The following species are regarded as authentic tako. Either historically, according to the area of distribution or according to the common practice in today's gastronomy: The term tako encompasses a variety of species that are grouped together under these names. Due to the extensive diversity of these species, it is not always possible to list all specific taxa in this list completely.

0

In the following, those species are listed that can be considered as substitutes for authentic species with regard to tako. This can be based either on their genetic relationship or on their similarity in taste and appearance. The selection is subjective and is not strictly based on Japanese conventions, but also takes into account the practices in the respective areas where the Japanese dishes are prepared. This flexible approach allows for adaptation to local availability and preferences while preserving the core flavor and texture traditionally associated with tako. This list is not exhaustive due to the possible diversity of species worldwide.

Sources and Further Reading

- [1]Sauer, W. H. H., Gleadall, I. G., Downey-Breedt, N., Doubleday, Z., Gillespie, G., Haimovici, M., … Pecl, G.. World Octopus Fisheries. Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture 29 (3) 279-429. 2021. DOI: 10.1080/23308249.2019.1680603.

- [2]東アジアに分布する商品価値が高いマダコの学名は Octopus sinensis d'Orbigny, 1841 (頭足綱: マダコ科) が妥当である. (abstract only, cf. English paper redescribing O. sinensis). . Taxa 41 55-56. 2016

- [3]Ian G. Gleadall. ctopus sinensis d'Orbigny, 1841 (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae): Valid Species Name for the Commercially Valuable East Asian Common Octopus. Species Diversity 21 (1) 31-42. 2016. DOI: 10.12782/sd.21.1.031.

- [4]Otilio Avendaño, Álvaro Roura, Celso Edmundo Cedillo-Robles, Ángel F. González, Rossanna Rodríguez-Canul, Iván Velázquez-Abunader & Ángel Guerra. Octopus americanus: a cryptic species of the O. vulgaris species complex redescribed from the Caribbean. Aquatic Ecology 54 909-925. 2020. DOI: 10.1007/s10452-020-09778-6.

- Hiroshi Hatanaka. Appendix 11 Spawning season of common octopus, Octopus vulgaris CUVIER, off the northwestern coast of Africa, Report of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Assessment of Cephalopod Stocks. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, 1979. Source retrieved 12/27/2020

- Patrizia Jereb, Clyde F. E. Roper, Mark D. Norman, Julian K. Finn. Cephalopods of the World. An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Cephalopod Species Known to Date, Volume 3. Octopods and Vampire Squids. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. 2014

- 『日本一の明石ダコ[ものしりコーナー] (The best Akashi Octopus in Japan (Monoshiri Corner))』. Akashi City Policy Bureau Public Relations Section (明石市政策局広報課). Source retrieved 12/27/2020

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2023-1

Image Credits

- City Foodsters (Grace Chen, Jason Wang). Tako (octopus) - Sukiyabashi Jiro, Tokyo, JP. flickr.com. Some rights reserved: Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

- SushiPedia. Tako Sushi. All rights reserved ©

- Non-disclosed author. big octopus swims in an aquarium. All rights reserved ©

- SushiPedia. Japanese Brands of Tako. All rights reserved ©

- SushiPedia. Major Catching Nations of True Octopuses in 2018. All rights reserved ©

- SushiPedia. The Art of Sushi Preparation: Featuring Yudako. All rights reserved ©

- Non-disclosed author. Tentacle of stew octopus on dark background.. All rights reserved ©

- Katsushika Hokusai. 蛸と海女の図. wikimedia commons. Some rights reserved: public domain

- SushiPedia. Global Capture Trends of True Octopuses. All rights reserved ©